|

| History of Canada |

Early British Rule

The British faced two immediate problems in the vast territory

that had thus been added to their other Atlantic colonies. There

were more than 60,000 new French-speaking subjects in what had

formerly been New France. In addition, there were large tracts

of thinly settled wilderness in the Great Lakes area where their

little garrisons were seriously outnumbered by the Indians.

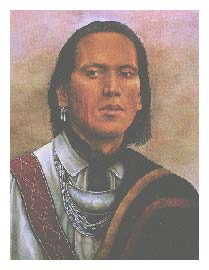

Odawa Chief, Pontiac |

Led by a clever and treacherous Ottawa chieftain named Pontiac,

the Indians suddenly rose against their new English masters

and overthrew these forts one by one, massacring the soldiers

in them without mercy. By the middle of 1763 the only British

soldiers left west of Lake Erie were in Fort Detroit. It alone

among the western forts held out against Pontiac until fresh

troops were rushed in, and the Indian uprising was subdued at

last.

The Quebec Act of 1774

Administration of the conquered province by a governor and an

appointed council was established by royal proclamation. In

1774 the English Parliament passed the Quebec Act. This was

the first important milestone in the constitutional history

of British Canada. Under its terms the boundaries of Quebec

were extended as far as the Ohio River valley. The Roman Catholic

church was recognized by the Quebec Act, and its right to collect

tithes was confirmed.

Also of enduring importance was the establishment of the French

civil law to govern the relations of Canadian subjects in their

business and other day-to-day relations with each other. British

criminal law was imposed in all matters having to do with public

law and order and offenses for which the punishment might be

fine, imprisonment, or in some cases death. These imaginative

gestures on the part of the English government won the admiration

of the religious leaders in Quebec and to a large extent the

goodwill of the people themselves. The privilege of an elected

assembly continued to be withheld, however.

The loyalty of the new province was soon put to the test. Within

a year of the passing of the Quebec Act, the rebelling 13 Atlantic

colonies sent two armies north to capture the "fourteenth colony."

Sir Guy Carleton, the British governor of Canada, narrowly escaped

capture when one of these armies, under Richard Montgomery,

took Montreal. Carleton reached Quebec in time to organize its

small garrison against the forces of Benedict Arnold. Arnold

began a siege of the fortress, in which he was soon joined by

Montgomery. In the midwinter fighting that followed, Montgomery

was killed and Arnold wounded. When spring came, the attacking

forces retreated. During the rest of the American Revolutionary

War, there was no further fighting on Canadian soil.

The United Empire Loyalists

When peace was established in 1783, many thousands of Loyalists,

who were referred to as Tories by their fellow countrymen, left

the newly created United States. They started their lives afresh

under the British flag in Nova Scotia and in the unsettled lands

above the St. Lawrence rapids and north of Lake Ontario. This

huge influx of settlers, who were known in Canada and England

as the United Empire Loyalists, marked the first major wave

of immigration by English-speaking settlers since the days of

New France.

Their arrival had two immediate consequences for the British

colonies. Both the Atlantic province of Nova Scotia and the

inland colony of Quebec had to be reorganized. The previously

unsettled forests to the west of the Bay of Fundy, once part

of French Acadia, had been included in Nova Scotia. In 1784

this area was established as a separate colony known as New

Brunswick. Cape Breton Island was simultaneously separated from

Nova Scotia (a division that was ended in 1820).

Arrival of the Loyalists |

In all, some 35,000 Loyalist immigrants are believed to have

settled in the Maritimes. The settlement of the more inaccessible

lands north and west of Lake Ontario and along the north shore

of the upper St. Lawrence proceeded somewhat more slowly. About

5,000 Loyalists came to this area. Upper and Lower Canada It

was clear that these United Empire Loyalists who had come to

the western wilderness of what was still part of Quebec would

not long be satisfied with the limited rights and French laws

established by the Quebec Act. Accordingly, in 1791 the British

Parliament enacted the Constitutional Act, whereby Quebec was

split into the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada. Each

of these was to be governed by a legislative council appointed

for life and a legislative assembly elected by the people.

The right to be represented in a lawmaking assembly was something

new for the French-speaking inhabitants of the lower province.

Legislative assemblies had been in existence in Nova Scotia

since 1758, in Prince Edward Island since 1773, and in New Brunswick

since 1786. Representative government, however, was not responsible

government, as was to be demonstrated before another 50 years

had passed.

Upper and Lower Canada

It was clear that these United Empire Loyalists who had come

to the western wilderness of what was still part of Quebec would

not long be satisfied with the limited rights and French laws

established by the Quebec Act. Accordingly, in 1791 the British

Parliament enacted the Constitutional Act, whereby Quebec was

split into the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada. Each

of these was to be governed by a legislative council appointed

for life and a legislative assembly elected by the people. The

right to be represented in a lawmaking assembly was something

new for the French-speaking inhabitants of the lower province.

Legislative assemblies had been in existence in Nova Scotia

since 1758, in Prince Edward Island since 1773, and in New Brunswick

since 1786. Representative government, however, was not responsible

government, as was to be demonstrated before another 50 years

had passed.

Settlement and Exploration

in the West

The Canadian prairies were not entirely unknown even in the

days of New France. As early as the 1730s a family of explorers

headed by Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Verendrye,

began a series of overland explorations far to the west of Lake

Superior. Their travels carried them into what is now the western

United States, perhaps as far as the foothills of the Rockies.

They visited Lake Winnipeg, the Red River, the Assiniboine River,

and the Saskatchewan River as far upstream as the fork formed

by the North and the South Saskatchewan. The posts of the Hudson's

Bay Company had given England a preferred jumping-off point

for exploration of the Canadian west. An expedition under Henry

Kelsey explored the territory between York Factory and northern

Saskatchewan in 1690, long before the journeys of the La Verendryes.

In 1754 Anthony Henday traveled from Hudson Bay as far as the

foothills of the Rockies, reaching a point near the site of

present-day Red Deer, Alta. Another Hudson's Bay Company trader,

Samuel Hearne, discovered Great Slave Lake in 1771, and by descending

the Coppermine River to its mouth, he became the first white

man to reach the Arctic Ocean by land. Although the Rockies

still barred the overland route to the western ocean, the Pacific

coast of Canada was visited by sea in 1778, when Capt. James

Cook explored the northwest coastline from Vancouver Island

to Alaska.

The Voyageurs |

In 1783 a group of Montreal merchants founded the powerful North

West Company. Not only did the new fur-trading company provide

sharp competition, but its trappers explored large parts of

the previously unknown expanses of the Canadian west. In 1789

Alexander Mackenzie (one of the Nor'westers) followed the river

which now bears his name from its source to the Arctic Ocean.

Disappointed because he had not discovered a route to the Pacific,

he set out on another expedition in 1792. After a strenuous

journey over the most rugged country on the continent, Mackenzie

and his companions at last crossed the Rocky Mountains to reach

the Fraser River in 1793. From the Fraser they portaged to the

Bella Coola, which they descended until they sighted the long-sought

western sea. Only a few weeks earlier Capt. George Vancouver

had explored the same part of the Pacific coast by sea. Mackenzie's

journey was the first made across the continent in either Canada

or the United States.

In 1808 the Fraser River was thoroughly explored by Simon Fraser,

after whom it is named. In 1811 David Thompson completed his

exploration of the Columbia from its source, in southeastern

British Columbia, to its mouth, in present-day Oregon.

The Selkirk Settlement

Although fur trading and settlement did not go well together,

Thomas Douglas, earl of Selkirk, became interested in the possibilities

of settling Scottish farmers who had lost their farms at home

in the fertile valley of the Red River near present-day Winnipeg.

From the Hudson's Bay Company he purchased a huge tract of 100,000

acres in this area.

In 1812 the first group of Selkirk's settlers from Scotland

and Ireland began to arrive from Hudson Bay, where they had

spent the previous winter. The jealousy of the Nor'westers,

as well as of the half-breeds, known as metis, was aroused immediately.

Fighting broke out between the new settlers and the established

traders. The colony was permanently established in 1817, when

Selkirk himself arrived with a force of military veterans to

put an end to the troubles and to punish the traders, whom he

held responsible for the bloodshed that had occurred. The North

West Company, a rival fur trading company, brought a lawsuit

against Selkirk for the action he had taken, and he was forced

to pay damages. Although Selkirk returned to Great Britain in

poor health in November 1818 and died a disappointed man a few

years later, he had begun the first permanent settlement on

the Canadian prairies.

The War of 1812

Meanwhile the British colonies far to the east found themselves

involved with the United States in a new war that threatened

to end their existence under the English flag.

Shawnee Chief, Tecumseh |

The declaration of war announced by the United States had several

causes. Chief among these was Britain's insistence on its right

to search American vessels for deserters from its own navy during

the war against Napoleon. In addition, England had interfered

with American trade with Europe. It was claimed too that the

British in Canada had been inciting the Indians against the

American settlements along the northwestern frontier. The early

hopes of the United States to drive the British entirely from

North America were dashed by a series of defeats at the hands

of British regulars and Canadian militia forces. Fort Michilimackinac,

at the entrance to Lake Michigan, was captured by the British

soon after the outbreak of fighting and was not recaptured during

the remainder of the war. An American attack across the Detroit

border was not only forced back but, under the brilliant generalship

of Gen. Isaac Brock, ably assisted by the Shawnee chieftain

Tecumseh and his warriors, was turned into a disastrous defeat.

The army defending Detroit was forced to surrender, and the

fort itself fell into British hands. Later the same year, the

United States launched an attack on the Niagara frontier. Brock

was killed early during the fighting at Queenston Heights, but

the invasion was repulsed.

Struggle for Self-Government

The successful defense of their homeland had not left the Canadians

incapable of seeing faults in their own form of government.

There were those--especially among the successful businessmen

and wealthier landowners--who believed that the colonists had

sufficient powers of self-government through their elected assemblies.

There were others, however, who saw little advantage in an assembly

whose bills could be defeated by the legislative council, or

could go unsigned by the governor on the advice of the executive

council. The real power did not lie in the hands of the people

through their elected representatives, but with appointed officials

who were responsible only to the government in Britain. In practice

the power lay in the hands of the governor and of his executive

advisers. The citizens could use their assembly as little more

than a forum in which to criticize the manner in which the government

was operated. Worse still, local matters that today are dealt

with by elected municipal bodies were all handled by the central

government of each colony.

Mackenzie and Papineau

Rebel

The period following the War of 1812 was one of expansion of

population, business, and settlement. This was especially true

in Upper Canada, where large numbers of newcomers were attracted

by low-cost land grants. The very growth of the colony offered

many opportunities for profit by those who could control the

land grants. One of the loudest accusers of the government's

administration of the land grants was William Lyon Mackenzie

(see Mackenzie, William Lyon). His criticisms centered on a

group that was known as the Family Compact. This was a loose

and somewhat misleading name for the members of the governing

class and their friends, among whom were actually many leaders

of great honesty and competence. Mackenzie, however, never clearly

understood the principles of responsible government by which

the executive would carry out the wishes of the government and

the government would hold office only so long as it had the

support of the people's elected representatives. Thus when the

government failed to redress the long series of grievances that

he listed, Mackenzie began to call for the independence of Upper

Canada. As affairs in Upper Canada moved toward a climax, an

equally serious crisis was building in Lower Canada. The grievances

were different, but the causes were similar. Here the real power

was in the hands of a British governor and his councilors, referred

to critically as the Chateau Clique, who constantly rebuffed

the elected representatives of the French-Canadian majority.

The leader of the radical reforms in Lower Canada was Louis

Joseph Papineau (see Papineau). Papineau, like Mackenzie, had

been several times elected to the provincial assembly. Like

Mackenzie, he had finally come to the conclusion that no lasting

reform could be achieved unless the bonds with Britain were

severed. Rioting occurred in Montreal in 1837. When the government

decided to arrest Papineau, he immediately fled across the border

to the United States. Largely because the radicals interpreted

this as persecution of their leader, open rebellion followed

in several centers. All revolts were quickly put down. Similar

troubles broke out in Upper Canada almost immediately. Mackenzie

prematurely called for an advance toward Toronto from his headquarters

just north of the city before his ill-equipped followers were

sufficiently well organized. The attack was driven back; and

the city, rapidly filling with Loyalist supporters, was fully

alerted. A few days later these forces marched northward against

Mackenzie and, after a short skirmish, dispersed his troops.

Like Papineau, Mackenzie fled across the United States border,

but he had not abandoned the struggle. Early in 1838 he took

possession of Navy Island in the Niagara River and, with a small

number of followers, tried to organize his planned republic

under what he spoke of as a "provisional government of Upper

Canada." The army and militia were now in full control of the

situation, and they forced Mackenzie to return to the United

States once again. Other disturbances followed along the border

during 1838. After a few unsuccessful raids, the United States

took steps to prevent its territory from being used for further

attacks against the Canadas. The struggle for reform was more

peaceful in the Maritimes. Here the leading reformers included

Joseph Howe, in Nova Scotia, and Lemuel Allan Wilmot, in New

Brunswick. Howe had a much clearer understanding of the principles

and advantages of responsible government than had either Mackenzie

or Papineau. Although he was persecuted for some of the criticisms

he voiced in his newspaper, the Novascotian, he rallied widespread

support. When sued for libel, he won his case.

The Durham Report

The seriousness of the troubles in British North America caused

deep concern in Great Britain, where memories of the American

Revolution could be recalled. At the request of Queen Victoria,

who came to the throne in 1837, John George Lambton, earl of

Durham, accepted appointment as governor in chief of British

North America with special powers as lord high commissioner.

He arrived in Quebec in the spring of 1838; though he ended

his stay before the year was out, his Report on the Affairs

of British North America is one of the most important documents

in the history of the British Empire. Durham recommended that

Upper and Lower Canada be united under a single parliament.

He said that if the colonies were given as much freedom to govern

themselves as the people of Great Britain, they would become

more loyal instead of less so. He even forecast the possibility

of a union some day of all the British colonies in North America.

His only serious error of judgment occurred when he said that

the French-speaking Canadians might be expected to be aborbed

by a growing English-speaking majority. Durham drove himself

and others tirelessly to gather the information he required

for his report during the few months he was in the country.

His political opponents at home, however, continued to attack

him, and, stung by their criticisms, he returned to England

to submit his findings. He did not live to witness the action

that was taken on his report, for within a year he became ill

and died.

Canada West and Canada

East

In 1840 the Act of Union was passed. It became effective the

next year and joined Upper and Lower Canada under a central

government. Henceforth the two colonies were to be known simply

as Canada West and Canada East, respectively. There was to be

an appointed upper chamber, or legislative council, in the new

government as well as an assembly composed of the same number

of elected members from each of the two old colonies. The seat

of government was established at Kingston; but after 1844 it

was moved to Montreal, then back and forth between Toronto and

Quebec, and finally to Ottawa in 1865. In the first several

years of this period, the principle of complete self-government

and the subordination of the governor's authority to that of

Parliament was developed and finally accepted. It was a critical

time in the constitutional history of Canada, and the ability

of the two chief Canadian nationality groups to get along with

each other was tested for many years. Each side produced great

public men. Prominent were Robert Baldwin from Canada West and

Louis Hippolyte Lafontaine from Canada East (see Baldwin, Robert).

Both men had taken part in the agitation preceding the rebellions

of 1837, but they had stood apart from the extreme measures

that led to armed insurrection. Both had grasped the meaning

of responsible government. By joining forces they formed a strong

coalition during the early years of the new government, and

the result was that much legislation was carried through. Included

were laws for establishing municipal governments, for founding

the University of Toronto as a nonsectarian institution, and

for changing the system of law courts. The real test of the

principle of responsible government took place in 1849. Parliament

passed the Rebellion Losses Bill, which had to go before the

governor-general, James Bruce, earl of Elgin, for his signature

to become law. The bill provided for compensation to those who

had suffered during the rebellion of 1837 in Lower Canada. It

was violently opposed by many of the Tories, who felt that tax

money was being turned over to former rebels. There was some

question as to whether or not Elgin would sign the bill as his

ministers advised him to do. When Elgin decided that he must

sign into law whatever bill was recommended to him by his Cabinet,

he was made the object of a torrent of abuse from the Tories.

Elgin's carriage was attacked, and his house was stoned. Furthermore,

rioting broke out, and the Parliament Buildings in Montreal

were razed by fire. Out of the ashes of the government buildings,

however, was born true colonial self-government that embodied

the principle of responsible cabinet rule.

The Colonies Grow Up

In the meantime Canada was swelling with settlers, and the foundations

of a British province on the west coast were being laid. A flood

of newcomers began to arrive after the War of 1812, mostly from

the British Isles. About 800,000 immigrants came to Canada between

1815 and 1850, sometimes spoken of as the period of the Great

Migration. The hardships faced by the new settlers were many.

The trials often began in the crowded, cholera-ridden, and poorly

provisioned sailing ships that brought the newcomers in vast

numbers across the Atlantic. The building of new settlements

went on in the Maritime Provinces and in the Canadas, and early

in the century Cape Breton Island was settled by Gaelic-speaking

farmers from the Scottish Highlands. The largest tracts of land

available for settlement were in Upper Canada, where the opening

of new subdivisions in the dense forests was an almost continuous

process during this whole period. One of the largest and most

famous of these was the huge tract of land on the north shore

of Lake Erie acquired by Thomas Talbot in about 1802. Established

in 1803, the Talbot Settlement was governed by him during the

whole period of its development, which covered almost 50 years.

In 1824 a large private enterprise known as the Canada Company,

promoted by John Galt, was launched with government backing.

Settlements began after the company obtained about 2.5 million

acres. Between 1824 and 1843 the company was responsible for

opening up most of the western part of the province lying north

of the Talbot country. Until the coming of the railway, the

principal method of moving heavy freight over long distances

was by water. Canals in the colonies were therefore improved,

and new ones were dug. Roads were cut through the bush to connect

the far-flung centers of settlement with lake and river ports.

On the backwoods farms great branding fires burned steadily

for weeks at a time as the pioneers slowly cleared their lands.

As a rule, the stumps were left in the ground to rot, which

required from five to six years for most woods. Cedar and pine

roots might hamper the use of horse-drawn plows for as long

as 15 to 20 years. In most respects pioneer life was very similar

in Canada and the United States.

|

|